Do You Have to Feed a Bearded Dragon Live Food

The nutrient requirements of reptiles is not well understood (Stahl and Donoghue, 2010). However, with the knowledge of veterinarians and scientific research, a well formulated bearded dragon diet is possible.

The bearded dragon diet varies from hatchlings, through to adults. As bearded dragons are generalists they eat a wide range of foods from invertebrates to vegetation. Providing a wide range of foods provides opportunities to gain a range of nutrients and reduce the risk of overdoing anti nutrients.

In the wild the bearded dragon diet for juveniles and younger is mostly invertebrates. As they become adults they move from the insectivorous diet to become omnivores. The adult bearded dragon diet is mostly vegetation.

Nutritional disorders in pet bearded dragon diets are very common and easily avoided. Nutritional disorders may be caused by environmental factors such as small enclosure size, poor lighting and heating, cohabitants, substrate or directly by food.

Consult your vet when formulating your bearded dragon diet. Your vet will be able to assess husbandry practices, state of health and other factors which influence the best diet for your bearded dragon.

Bearded Dragon Safe Food Lists

Bearded dragons are best provided a wide range of vegetation to maximise opportunities for nutrients and reduce the risk of overdoing antinutrients. The following safe food list for bearded dragon diet has been compiled with data from researchers and veterinarians.

99+ Vegetables, Leafy Greens and Fruits

Legend: O Feed often O Feed sometimes O Feed small portions sometimes

O Alfalfa greens & sprouts

O Apples

O Apricots

O Asparagus

O Bananas

O Basil

O Beans common, snap, green

O Beet greens

O Beets boiled

O Berries – blackberries, blueberries, boysenberries, cranberries, elderberries, raspberries, mulberries, gooseberries

O Bok choy, Bok choi, Pak choy, Pak choi (chinese cabbage)

O Broccoli florets, flowers and leaves

O Broccoli rabe (Rapini)

O Brussels sprouts

O Cabbage red, savoy

O Cactus flowers

O Capsicum sweet/bell peppers

O Carrot grated / boiled

O Carrot tops

O Cauliflower

O Celery

O Cherries sweet

O Cilantro (coriander) leaves

O Clover

O Collard greens

O Commercially prepared food

O Corn sweet

O Cucumber

O Currants

O Dandelions

O Endive Escarole chicory

O Figs

O Grape leaves

O Grapes

O Grasses – Bermuda, Timothy, Kentucky bluegrass, Buffalo

O Guava

O Hibiscus leaves

O Kale

O Kiwifruit

O Lettuce Boston, Romaine, Cos, red

O Mango

O Melons – honeydew, rockmelon, cantelope, watermelon, strawberries

O Mulberry leaves

O Mung beans (sprouted)

O Mustard greens

O Mustard spinach

O Nectarine

O Okra

O Papaya (paw paw)

O Parsley

O Passionfruit (purple)

O Peach (yellow)

O Pears

O Peas

O Peas, green, podded

O Pineapple

O Plum

O Potato

O Prickly pear pads & fruits

O Primroses

O Pumpkin butternut squash

O Pumpkin leaves

O Radish greens

O Raisins

O Rutabaga (swede)

O Silverbeet leaves (Swiss chard)

O Spinach

O Squash – zucchini, courgette, marrow, winter acorn, button

O Sweet potato

O Sweet potato leaves

O Turnip greens

O Turnips

O Vegetables, mixed, frozen

O Watercress

O Weeds

12 Edible Flowers Bearded Dragons Can Eat

Bearded dragons can eat flower in moderation like all other vegetation as part of a varied diet. Here are 12 flowers bearded dragons can eat:

- Broccoli flowers

- Cactus flowers

- Carnations

- Dandelion flowers

- Geraniums

- Hibiscus flowers

- Nasturtiums

- Pansies

- Petunias

- Primroses

- Pumpkin & squash flowers

- Roses

Data is averaged. Nutritional composition data for Excel table derived from the following sources:

Australian Food Composition Database, 2019; USDA Food Composition Database; Rop et al, 2012; Kuhnlein & Turner, 1996; Carlson et al, 1987; Vieites-Outes et al, 2015; Béliveau and Gingras, 2017; Bheemreddy and Jeffery, 2006; Akhtara et al, 2010; Erdogan and Onar, 2011; Abdel-Moemin, 2014; Tsai et al, 2005; Al-Wahsh, 2012; Holmes & Kennedy, 2000; Honow and Hesse, 2002; Jean et al, 2018; Zarembski and Hodgkinson, 1962; Jèhanno and Savage, 2009; Savage, et al 2018; Vu Hong Ha, 2012; and Hejduk and Dolezal, 2004.

25+ Insects to Feed Bearded Dragons

25 insects and other invertebrate that can be fed to bearded dragons include:

- Black Soldier Fly (Phoenix worms) (high in calcium)

- Butterworm

- Hornworms

- Mealworms

- Waxworms

- Superworm

- Silkworms pupae and moth

- Cockroach American, Dubia, Madagascar hissing, woodies, Turkestan

- Cowpea weevil

- Earthworms, red wriggler worms (high in calcium if fed on calcium rich soil (Divers and Mader, 2005))

- House flies & larvae (bred for the purpose)

- Fruit flies

- Crickets

- Grasshoppers

- Cicadas

- Katydids

- Locusts

- Lacewings

- Slater, Pillbug, Sowbug, Woodlouse, Woodlice

- Slugs

- Snails

- Spiders

- Stick insects

- Termites

- Sweeping insects, moths and grubs (wild caught)

Without an endoskeleton few invertebrates contain a sufficient calcium, however they have sufficient phosphorus (Divers and Mader, 2005).

Feeding live insects to bearded dragons, particularly young ones, provides an ideal opportunity for natural enrichment (Divers and Mader, 2005). If the enclosure is not a suitable environment to feed in (i.e. it has a loose substrate) then a large container can provide a suitable alternative. Feeding in a large container also makes it easier to collect uneaten insects after feeding.

If feeding insects in the enclosure, remove uneaten insects when feeding time is over. Some insects, such as crickets, have a reputation for eating the predator. This will likely start in moist areas such as eye lids and the nose.

The nutritional quality of the insects is important. Gut loading insects is useful for specifically targets nutrients required by bearded dragons, not the insects. Nutrients such as calcium cause mortality in some invertebrates within days. This is a major reason gut loading is only performed within a day prior to feeding to your reptile.

| Rusty Red Cockroach nymphs – Blatta lateralis |  |  | Black Soldier Fly larvae – Hermetia illucens (aka Reptiworm) |  | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated # per 2.5 g | 6 | 5 | 2 | 30 | 18 |

| Moisture | 1.73g | 1.73g | 2.07g | 1.53g | 1.59g |

| Protein | 0.48g | 0.51g | 0.23g | 0.44g | 0.59g |

| Fat | 0.25g | 0.17g | 0.04g | 0.35g | 0.14g |

| Calcium | 0.96mg | 1.02mg | 0.44mg | 23.35mg | 0.58mg |

| Phosphorus | 4.40mg | 7.38mg | 5.93mg | 8.90mg | 6.93mg |

Superworm – Zophobas morio |  Waxworms – Galleria mellonella | Earthworms – Lumbricus terrestris |  Butterworm – Chilecomadia moorei | Mealworms larvae – Tenebrio molitor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated # per 2.5 g | 4 | 8 | 12 | 6 | 20 |

| Moisture | 1.45g | 1.46g | 2.09g | 1.51g | 1.55g |

| Protein | 0.49g | 0.35g | 0.26g | 0.39g | 0.47g |

| Fat | 0.44g | 0.62g | 0.04g | 0.74g | 0.13 g |

| Calcium | 0.44g | 0.61mg | 1.11mg | 0.31mg | 0.42mg |

| Phosphorus | 5.93mg | 4.88mg | 3.98mg | 5.63mg | 7.13mg |

Complete nutrient content of four species of feeder insects, Zoo Biology 00:1-15 M D Finke, 2012. Complete nutrient composition of commercially raised invertebrates used as food for insectivores, Zoo Biology 21:269-285, M D Finke, 2002

Food List Sources

The bearded dragon food lists have been compiled from veterinary and researcher recommendation. Specifically the following sources:

Brown, 2012; Johnson, 2006; Stahl, 1999; UCDavis, 2019; Mitchell and Tully, 2008; Stahl and Donoghue, 2010; Girling, 2013; Divers and Mader, 2005; Finke, 2012; Boyer, 2015; and NC State Veterinary Hospital.

Commercial Diets

Commercial diets are not regulated and do not necessarily provide the nutrients claimed by manufacturers (Mitchell & Tully, 2008). However, commercial diets have improved and reduce the risks of imbalanced diets prepared by pet owners (Stahl and Donoghue, 2010).

Can I feed my Bearded Dragon Wild Insects?

Wild insects can be fed to bearded dragons (Stahl and Donoghue 2010). It is part of a recommended diet by some our most influential doctors of veterinary science for bearded dragons and referred to as 'sweepings', as you sweep the grass with a net.

Ensure the sweepings do not contain poisonous invertebrate and have not been contaminated with poisons (i.e. pesticides and herbicides).

Can bearded dragons have egg?

Bearded dragons can have cooked egg for protein (Stahl and Donoghue, 2010). Boiled eggs were added to the diet of bearded dragons at the Philadelphia Zoo in very small portions. An entire salad split between multiple reptiles included approximately 9 boiled eggs to approximately 10 kg of vegetation. (Bentley et al, 1997). That is less than 1 egg per kilo of vegetation.

Diet and How Often to Feed

What do baby bearded dragons eat?

Baby bearded dragons eat small insects such as nymph crickets and cockroaches. They start out life as insectivores and enjoy a range of active invertebrate, unlike the adults which prefer more sedate or slow foods.

Johnson (2006) recommends moths, flies, small crickets, small grasshoppers, soldier fly larvae, mealworms and other grubs. Some vegetation may be offered however the majority of their food should be insects as they start out life as insectivores.

Hatchlings or neonate bearded dragons are ready to eat invertebrates within a day or so of hatching. Baby bearded dragons do not need vegetation.

Baby bearded dragons are going through rapid growth and need calcium and to support them. Mistakes at this age with lighting, calcium and D3 can quickly lead to metabolic bone disease.

Sunshine without anything in between the bearded dragon and the suns UVB rays is far better than any supplementation and is likely to reduce the impact of mistakes with UVB lighting. See the post Guide to Calcium and D3 by Dr Ahmad

How often to feed baby bearded dragon

Baby bearded dragons may be fed multiple times a day.

| Feeding Frequency | Source |

|---|---|

| Feed multiple times daily | Johnson, 2006 |

What do juvenile bearded dragons eat?

Juvenile bearded dragons eat mostly insects but will also eat some vegetables and fruit.

Bearded dragons start to switch from being insectivores to omnivores in the juvenile stage. In the wild, bearded dragons have been found to eat vegetation only when they reach 80-100 mm (3-4 inches) (Wotherspoon, 2007).

Juvenile bearded dragons eat active prey and this is good for activity and exercise.

Brown (2012) recommends juvenile bearded dragons should be fed 50% insects and 50% plant matter. As the bearded dragon moves closer to adulthood the vegetation should be increased and arthropods reduced.

Juveniles are vulnerable to metabolic bone disease. More on preventing MDB in the post Metabolic Bone Disease and What to do About It by Dr Buchanan. Sunlight is a major key to absorption of calcium.

How often to feed juvenile bearded dragon

Feed juvenile bearded dragons 1-2 times a day at around 3 months of age (Brown, 2012; Stahl and Donoghue, 2010), reducing to 5-7 times a week by 6 months old (Brown, 2012).

| Feeding Frequency | Source |

|---|---|

| Feed 1-2 times a day (3-4 months old) Feed 5-7 times a week (6 months old) | Brown, 2012 |

| Feed 1 – 2 times a day | Stahl and Donoghue, 2010 |

What do adult bearded dragons eat?

Adult bearded dragons eat leafy greens, vegetables, fruit and insects. At this age they are fully omnivores leaning towards the majority of the diet being vegetation.

Vegetation makes up approximately 75% of the diet with leafy greens making up the majority of that and 25% invertebrate (NC State Veterinary Hospital). Vegetables, not leafy greens, can make up to 20% of the diet (Stahl and Donoghue, 2010).

For omnivore lizards (i.e. bearded dragons) Stahl and Donoghue (2010) recommend between 60 to 75% of the diet may be a commercially prepared food. Providing this level of a commercially prepared bearded dragon diet should not require further supplementation of vitamins and minerals.

An excess of invertebrates is not seen in the wild bearded dragon diet. Wotherspoon (2007) was able to study the stomach content of wild bearded dragons. The research showed a lot of vegetation is eaten in the wild by adults, 90% plus with males eating more vegetation than females. Wild bearded dragons do not eat active insects and instead eat ants and other easy to capture invertebrates.

Be flexible in the quantity fed and adjust as required to suit the needs at the time. Daily feeding, providing smaller frequent meals rather than one bulk meal works well for many insectivorous, herbivorous and omnivorous lizards in their active times of the year (Voe 2014). Take caution that this does not lead to the temptation to feed a greater quantity. Four factors that may influence the quantity and frequency of feeding include:

- biological state – growing, gravid, shedding

- brumation

- environment

- current condition – health, overweight, underweight

Simpson (2015) recommends adding some native Australian vegetation such as Eremophilas sp., Hemiandra pungens, Croweas, Correas and Grevilleas.

Some bearded dragons are not so easy when it comes to eating vegetables. For ideas on how to get your bearded dragon to eat vegetables see the post how to get your bearded dragon to eat greens.

How often to feed adult bearded dragon

Adults can be fed every day to every other day (Stahl and Donoghue, 2010; NC State Veterinary Hospital; Johnson 2006). Bearded dragons that are pregnant, ill, or some other taxing biological state will require different feeding regimes. Discuss with your vet.

| Frequency | Source |

|---|---|

| Feed 2 – 4 times a week | Brown, 2012 |

| Daily to every other day | Stahl and Donoghue, 2010; NC State Veterinary Hospital |

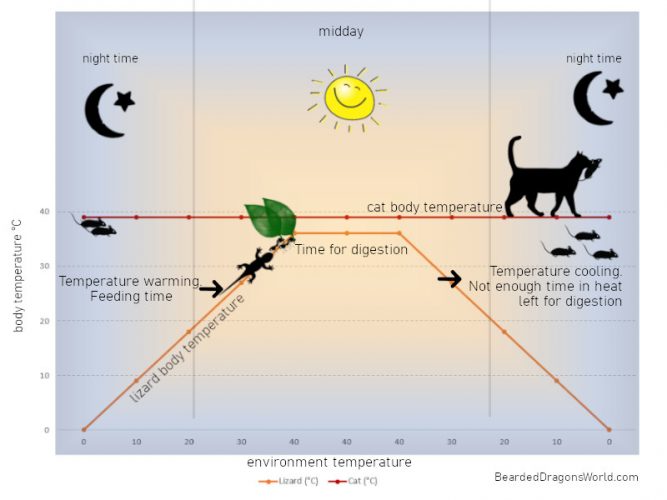

When Should I Feed?

Bearded dragons should be fed at the same time that it needs to bask (Stahl and Donoghue, 2010). Allow hours in between feeding and when the temperature will go back down for the day to ensure adequate time for digestion.

For more activity opportunities spread the feeding out over many hours in the 'heat of the day' as long as the volume of food does not increase.

For reptiles the POTZ (preferred optimum temperature zone) is very important for the digestion of food. If the temperature is too low, it will adversely affect its ability to process the food and could result in malnutrition if not rectified. Bearded dragons need at least a couple of hours of 'day' temperatures after the end of a feed to digest.

How Much to Feed

Bearded dragons require approximately 5% of its ideal body weight, give or take, in food.

For reptiles it is generally accepted that they have 10% of the energy requirements as that of mammals (Voe 2014). This is important to keep in mind when assessing volumes and food types.

Making Meals Convient by Freezing Bearded Dragons Foods

Foods can be prepared and frozen ahead of time for feeding bearded dragons ( Stahl and Donoghue, 2010). Freezing foods ahead of time not only makes feeding a lot more convenient when it comes to feeding time, but also makes it more economical to purchase a wide range of foods for creating meals. Frozen meals for bearded dragons is convenient.

Foods that can be frozen for bearded dragons include some invertebrate such as maggots (Brown, 2012), vegetables and fruits.

There may be some nutrition loss with frozen vegetables and fruit. However, freezing may assist in making some nutrients more available as it can break down cell walls (Divers & Mader, 2005).

How to Prepare Foods for Feeding

Leafy greens and fruits do not need any preparation for feeding apart from washing. Hard foods can be lightly cooked or grating.

Hard bodied insects and rough vegetation is better for teeth than soft foods that can linger in the mouth for long periods of time. See the post bearded dragons teeth and disease for more information on periodontal disease.

Chopping Food

Chop food no bigger than the distance between the bearded dragon eyes, preferably small. Some foods can be sliced rather than cubes which may encourage biting into the foods. Biting the foods will give a rough surface for the teeth to aid in keeping them clean.

Slicing portions that are too large to swallow without the bearded dragon breaking them up may also slow down feeding time. This will give a longer period of activity and potentially reduce the risk of obesity (post here on ways to stop your bearded dragon getting fat).

2 Reasons to Cook Bearded Dragon Vegetables

Here are 2 reasons to cook foods for bearded dragons:

- Reduce antinutrients such as oxalates and trypsin inhibitors

- Soften hard foods

Cooking may reduce some antinutrients such as oxalates or trypsin inhibitors (such as in sweet potato). Oxalates are not necessarily an issue, see the section on Oxalates on this page for further information. Trypsin is an enzyme involved in the breakdown of many different types of proteins including as part of digestion.

The main reason to cook foods for bearded dragons is to soften hard vegetables, such as carrots and pumpkins.

When cooking foods for bearded dragons, don't cook them all the way. The foods should remain firm, not hard. Foods that are too soft stay in the mouth longer and can contribute to periodontal disease.

Do not cook foods that do not need to be. Cooking can also reduce desirable nutrients, such as thiamin. Vegetation should not generally be cooked, especially leafy greens (Divers & Mader, 2005). Alternatively hard vegetables grated.

Preparing Sweet Potato

Bearded dragon diet may include sweet potato, however sweet potato have trypsin inhibitors which may need to be inactivated before feeding.

Cooking sweet potato at temperatures of at least 90°C (194°F) or higher for several minutes is sufficient to inactivate trypsin inhibitors (FAO 1990). At lower temperatures the trypsin inhibitors may not deactivate. For context, water boils at 100°C (212°F).

Sweet potato can be cooked in the microwave, dry heat of the oven or in a pot of water. Do not add oil.

Dusting Invertebrate

Invertebrate should be dusted before feeding. For invertebrate that supplements stick to well they may be dusted in a bag. For invertebrate that powders do not stick to so well, such as mealworms, place them in a shallow bowl with calcium powder and offer to your bearded dragon.

Invertebrate may be coated with a vitamin and mineral power once or twice a week.

The amount of calcium supplementation is dependent on multiple factors including age, gravid and so on which is covered in depth in the post on guide to calcium and D3 with DVM Amna Ahmad.

Research by Michaels et al (2014) found that dusting can increase the Ca:P (calcium to phosphorus) ratio of crickets to 1:1 regardless of the calcium supplement powder used. Three (3) different commonly available calcium supplementation powders available for reptiles were used in the experiment. The varying levels of calcium in the calcium powder did not significantly affect the overall results. The Ca:P ratio could be maintained on the crickets for up to 5.5 hours post dusting.

Michaels et al (2014) research also warns that extremely high levels of calcium are present on the crickets immediately after dusting. With other nutritional components in supplements this may result in harm over the longer term. More is not better.

Why There is so much Variation in Food Data

Having access to scientific and research data means you can remove confusion and make informed decisions. International and national food databases and research have been used for the data in this article however, it is best viewed as generalisation only.

National food databases and research across the world provide different data on foods. There are many factors that can influence the level of nutrients and anti nutrients recorded for any fresh produce including:

- the way in which it was tested,

- fertilisers used,

- the condition of the soil,

- the time of day it was picked,

- conditions of transportation,

- whether it is new leaves or old,

- the cultivar.

One example of just how much data can vary is with a study Mason et al (2000) published. A huge variation of oxalate in the same spinach cultivar (Winter Giant) was found with tests by Mason et al (2000) showing 400-600 mg/100 g fresh weight whereas Gontzea and Sutzescu (cited in Mason et al, 2000) came in at double, 700-900 mg/100g.

Bearded Dragon Diet and Link to Disease

Excessive Foods, High Fat and Sugar Diets

Overfeeding and feeding diets high in fats and sugars can quickly lead to overweight, fat bearded dragons. Bearded dragons have not evolved to be able to cope with excess weight and this will likely translate to disease.

Gimmel et al (2017) conducted a number of surgeries and autopsies on bearded dragons. The study found that a bearded dragon diet excessively rich in fat and protein is causing a rise in gallstones. The bearded dragons in the study had a diet high in insects mostly mealworms, superworms, crickets and locusts.

Bearded dragons are ectotherms, meaning they rely on the environment for their temperature. Humans are endothermic, we can expend 80% of our energy regulating our warmth. As bearded dragons are efficient with their use of energy, adults can easily miss a day here and there of food. This is far more likely to match their normal states in the wild than having large meals multiple times a day. For more on fat in bearded dragons see the post Is my Bearded Dragon Fat or Skinny?

Fruit should only be fed in small portions, 5% of the diet or as a treat. This is mainly due to the high sugar content of fruits grown for the human taste. However, another problem with fruit is that it is typically soft and mushy. Soft foods have more places they can get trapped in the mouth and stay for longer which can quickly lead to periodontal disease which is very common in bearded dragons.

Damage to bearded dragons teeth will often show as swellings in the mouth, brown teeth and gums. As the disease worsens the teeth and gums may become black. Sometimes periodontal disease isn't obvious at all, as the Melbourne Zoo found out back in 1989. For more on protecting teeth see the post on teeth and disease.

Antinutrients in Foods

Compounds such as oxalates, goitrogens and tannins are typically considered anti nutrients in the bearded dragon diet however, this is not necessarily the case.

Foods high in oxalates and goitrogens may be safe to feed bearded dragons and other lizards.

Why are foods with oxalate considered a problem?

Oxalate (oxalic acid) is a natural compound of foods. Oxalate binds to calcium and trace minerals as food moves through the stomach and intestines, eventually leaving the body in stools. When the minerals are bound by oxalate, it is no longer available for the body to absorb.

As with all nutrients and antinutrients, oxalate data varies significantly from one source to another. Some of the major contributing factors to the variable data are conditions such as season, soil and harvesting practices (Attalla et al, 2014).

Doneley et al (2018) advise that there are no studies which verify oxalate compounds in herbivorous reptile diets makes calcium unavailable. In humans we have some level of bacteria that can break down some of the oxalate before it can activate binding minerals (Spritzler, 2017). Herbivorous mammals are also able to break down oxalates leaving calcium available for absorption (Doneley et al, 2018). Boyers (2015) echo's that advice extending the choice of foods to those high in oxalates.

Foods high in oxalates also have important nutrients. Removing them completely from the diet would reduce the variety of foods and mean the important nutrients are also not offered.

Oxalate content is considered high for humans when it reaches 100 – 900 mg per serving (Spritzler, 2017).

Foods high in oxalates include:

- Silverbeet or Chard

- Asparagus

- Spinach

- Beet greens

- Brussels sprouts

- Grape leaves

Goitrogens and Brassicas

Doneley et al (2018) advise that while Brassicas contain thiocyanate which is a concern for iodine uptake, it is rarely an issue in reptiles.

Stahl and Donoghue (2010) are in favour of providing foods that contain oxalate and goitrogens but suggest limiting the quantities. Mitchell & Tully (2008) recommend feeding foods high in glucosinolates sporadically (Mitchell & Tully, 2008). If unsure, discuss with your vet.

Boyer (2015) warns that removing members of the Brassica family is not necessary and based on misconceptions. Boyer advises that Brassica vegetables ability to cause thyroid problems (goiter) are not proven and are suitable for feeding as part of a balanced diet. Boyers (2015) advise extends to foods high in oxalates.

Providing a range of foods in the bearded dragon diet is the best defense.

Foods high in goitrogens include:

- Cabbage

- Mustard greens

- Kale

- Broccoli

- Brussels sprouts

- Radish greens.

Tannins

Tannins naturally occur in many plants. Tannins bind and precipitate proteins. Tannins are found in many fruits (grapes, bananas, peaches, apples, blueberries, etc) and other vegetation such as (mint, basil, Acacia spp, and corn).

Foods Dangerous for Bearded Dragons

- Fatty foods – impede calcium metabolism

- Avocado

- Rhubarb

Do Bearded Dragons Chew Their Food?

What Do Bearded Dragons Eat in the Wild?

Bearded dragons eat in the wild a range of leaves, flowers, fruits and invertebrates.

Oonincx et al (2015) studied the stomach content of 10 adult bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). Their research found that just over 60% was made up of invertebrates with 95% of that being termites. Invertebrates that made up the remainder included spider, locust, centipede, dragonfly and mosquitos.

Interestingly the research by Oonincx et al (2015) also showed a very small portion, 2.3%, of indigestible material in the stomach. The indigestible material included plastic, grit and degraded bone. The study proposed that the degraded bone could potentially be an aid for how bearded dragons get calcium in the wild. For more on calcium see why we dust insects for bearded dragons when they don't get it in the wild.

Thompson and Thompsons (2003) studied the Pogona minor. In their research they noted that some of the bearded dragons were moving between bull ant mounds and one was found with a mouth full of bull ants it was eating. Their study did not delve further into the stomach content.

Pianka (2005) published observations of Pogona minor (Dwarf Bearded Dragons) that he collected over a period of almost 40 years. His observations of what the Dwarf Bearded Dragon eats in the wild included grasshoppers, beetles, termites, insect larvae, ants, wasps, phasmids and other bugs. Grasshoppers made up the majority of the diet at 30%, beetles 17% of the diet and termites almost 12% of the diet.

Plant matter of the Dwarf Bearded Dragon was as low as 21% of the diet being a mix of grass, seeds, bark, flowers and other plant material that was not identified.

Rose (cited in Wotherspoon 2007) went through the stomach content of 5 wild Pogona barbata killed on the roads. The wild bearded dragons diet was found to include a range of cockroaches, grasshoppers, locusts, weevils, ants, bull ants (Myrmecia gulosa and Myrmecia tarsata), katydids, matchstick grasshoppers, dung beetles, Christmas beetles and bees. The vegetation was not described.

Wotherspoon (2007) studied the stomach contents of 89 free ranging wild bearded dragons (Pogona barbata). The bearded dragons were found to eat a range of invertebrate. The invertebrate ranged from 50% ants to the rarest of the invertebrates which were centipede, grasshopper, locust and caterpillar (total of 7 in the entire range). Dandelion and clover were the main vegetation both of which are introduced species, not native to Australia. Other vegetation included flowers, Kangaroo grass (Themeda australis), Glycine spp and Xanthosia spp.

Incidentally dandelions are very high in protein. Research by Ghaly et al (2012) found dandelions to contain 4.70% protein. As a comparison, apples had 0.26% and sweet potato 2.57%.

The invertebrate that Wotherspoon (2007) found most commonly eaten by adult wild bearded dragons were those that are easy to catch such as ants and beetles. However, the majority of the diet was plant matter. The vegetation was not chewed but found in pieces of 3-5 mm long.

Wild juvenile bearded dragons were found with plant content only after reaching a snout to vent size of 80-100 mm (3-4 inches). Their choice of invertebrate included much more active species than adults including grasshoppers and locusts.

Wotherspoon and Shelley (2016) found that there were differences in the bearded dragon diet between females and males. Male bearded dragons also had a difference in diet depending on size. Females fitted within the typically omnivore type of profile and ate a lot of ants. The males ate a large proportion of vegetation, with the larger the male the higher the proportion of vegetation to a point of being herbivores. None of the vegetation had been chewed and the main insect eaten by any adult was ants (unlike juveniles).

Previously Wotherspoon (2007) found the vegetation content of some adults was so high (90% or more) that it was suspected that the odd insect was consumed (mostly ants) by accident while eating vegetation.

Wotherspoon and Shelley (2016) found that juvenile bearded dragons ate active prey including flying invertebrates. Juveniles require a high protein diet that supports growth. Females need higher levels of protein and fatty acids than males for reproduction purposes.

6 herbs, grasses and vegetation eaten by wild bearded dragons:

- Dandelions

- Clover

- Flowers

- Grasses (Kangaroo grass – Themeda australis)

- Glycine spp

- Xanthosia spp

17 invertebrates and insects eaten by wild bearded dragons:

- Termites

- Ants

- Dragonflies

- Mosquitoes

- Cockroaches

- Weevils

- Caterpillars

- Locusts

- Grasshoppers

- Katydids

- Matchstick grasshoppers

- Beetles (including dung beetles and christmas beetles)

- Bees

- Wasps

- Spiders

- Centipedes

- Insect larvae

Wild Bearded Dragon Diet Conclusion

The wild bearded dragon diet (Pogona vitticeps and barbata) includes a range of invertebrates and plants. Bearded dragons are essentially insectivores until they reach adulthood at which point they become omnivores. The plant matter eaten by male wild bearded dragons is so significant that they are almost herbivores.

The same may not be the case for the Pogona minor which may prefer a higher ratio of invertebrate throughout its life than plant matter.

Other related articles are 'can bearded dragons eat mice?' and 'techniques to get bearded dragons to eat vegetables'.

Can bearded dragons eat dog food? The Department of Environment and Science breakdown the minimum diet for a bearded dragon which includes eating small quantities of moistened dry dog food.

More Articles

References and Further Reading

- Abdel-Moemin, A. R. (2014) Oxalate Content of Egyptian Grown Fruits and Vegetables and Daily Common Herbs. Journal of Food Research. 3(3)

- Akhtara, M. S., Israrb, B., Bhattyb, N., and Alic , A. (2010) Effect of Cooking on Soluble and Insoluble Oxalate Contents in Selected Pakistani Vegetables and Beans. International Journal of Food Properties. 14(1): 241-249

- Akhtara, M. S.; Israrb, B.; Bhattyb, N.; Alic, A. (2010) Effect of Cooking on Soluble and Insoluble Oxalate Contents in Selected Pakistani Vegetables and Beans. International Journal of Food Properties. 14: 1, 241-249

- Al-Wahsh, I. A. (2012) A Comparison of Two Extraction Methods for Food Oxalate Assessment. Journal of Food Research. Vol 1 (2)

- Aly R. Abdel-Moemin. (2014) Oxalate Content of Egyptian Grown Fruits and Vegetables and Daily Common Herbs. Journal of Food Research; 3(3)

- Attalla, K., De, S., & Monga, M. (2014) Oxalate Content of Food: A Tangled Web. Urology 84(3): 555-560

- Aucone, B. (Ed), and Peeling, C. (Ed). (2012) Regional Collection Plan. Association of Zoos and Aquariums. AZA Lizard Advisory Group. Revised

- Australian Food Composition Database

- Béliveau, R. & Gingras, D. (2017) Foods to Fight Cancer: What to Eat to Reduce Your Risk. 2nd Ed. DK Penguin Random House

- Bentley A, Toddes B, and Wright K. (1997) Evolution of diets for Herbivorous and Omnivorous Reptiles at the Philadelphia Zoo: From Mystery Toward Science. Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Zoo and Wildlife Nutrition, AZA Nutrition Advisory Group, Fort Worth, TX.

- Bheemreddy, R. M., & Jeffery, E. H. (2006) Occurrence and Distribution of Glucosinolates in Edible Plants. Nutritional Oncology (Second Edition) Chapter 34 Pages 583-596

- Boyer, T. H. (2015) Diseases of Bearded Dragons. AV017

- Boyer, T. H. (2015) How to Feed Reptiles Right. AV007

- Brown, D. BVSc (Hons) BSc (Hons) (2012) A Guide to Australian Dragons in Captivity. Reptile Publications, QLD.

- Carlson, D. G., Daxenbichler, M. E., VanEtten, C. H., Kwolek, W. F., and Williams, P. H. (1987) Glucosinolates in Crucifer Vegetables: Broccoli, Brussels Sprouts, Cauliflower, Collards, Kale, Mustard Greens, and Kohlrabi. Journal of American Society Horticulture Science. 112(1): 173-178

- Department of Environment and Science. Captive reptile and amphibian husbandry. Code of Practice Wildlife Management. Queensland Government.

- Divers, S. J., and Mader, D. R. (2005) Reptile Medicine and Surgery – E-book. Elsevier Health Sciences

- Doneley, R., Monks, D., Johnson, R. & Carmel, B. (2018) Reptile Medicine and Surgery in Clinical Practice. John Wiley & Sons.

- Durowoju, O. (2014) Oxalate content of some Nigerian tubers using titrimetric and UV spectrophotometric methods. Academia Journal of Agricultural Research 2(2)

- Erdogan, B. Y.,and Onar, A. N (2011) Determination of Nitrates, Nitrites and Oxalates in Kale and Sultana Pea by Capillary Electrophoresis. Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances 10 (15): 2051-2057

- FAO. (1990) Roots, tubers, plantains and bananas in human nutrition. 7. Toxic substances and antinutritional factors. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Ghaly, A. E., Mahmoud, N., & Dave, D. (2012). Nutrient Composition of Dandelions and its Potential as Human Food. American Journal of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 8 (2), 118-127.

- Gilani, G. S., Xiao, C. W., and Cockell, K. A. (2011) Impact of Antinutritional Factors in Food Proteins on the Digestibility of Protein and the Bioavailability of Amino Acids and on Protein Quality. British Journal of Nutrition 108, S315–S332.

- Gimmel, A., Kempf, H., Öfner, S., Müller, D., and Liesegang, A. (2017) Cholelithiasis in adult bearded dragons: retrospective study of nine adult bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps) with cholelithiasis between 2013 and 2015 in southern Germany. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 101 (Suppl. 1)(2017) 122–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpn.12616

- Girling, S. (2013) Veterinary Nursing of Exotic Pets. Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118782941

- Gupta, R. C. (2007) Veterinary Toxicology: Basic and Clinical Principles. Elsevier. London, UK.

- Hejduk, S., and Dolezal, P. (2004) Nutritive value of broad-leaved dock (Rumex obtusifolius L.) and its effect on the quality of grass silages. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 49(4): 144–150

- Holmes, R. P., & Kennedy, M. (2000) Estimation of the oxalate content of foods and daily oxalate intake. Kidney International. Vol 57(4) 1662-1667.

- Honow, R. and Hesse, A. (2002) Comparison of extraction methods for the determination of soluble and total oxalate in foods by HPLC-enzyme-reactor. Food Chemistry. 78: 511-521

- Jean, K., Odon, M., Seraphin, M., Maurice, N., and Kindala, J. (2018) A Study of Oxalate Content of Some Selected Species of Hibiscus Cultivated in Kwilu State/Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Scientific Research and Reports. 19: 1-7

- Jèhanno, E and Savage, G. (2009) Oxalate content of commercially packed salad greens. Journal of Food, Agriculture and Environment. Vol 7 (3&4): 207-208

- Johnson, J. D. (DVM) (2006) Exotic DVM. Care of Bearded Dragons. 8(5) pages 38-44. Zoological Education Network

- Kuhnlein, H. V. & Turner. N. J. (1996) Traditional Plant Foods of Canadian Indigenous Peoples Nutrition, Botony and Use. Food and Nutrition in History and Anthropology. Vol 8. Gordon and Breach Publishers

- Lemm, J. M., Lung, N. (DVM), and Ward, A. M (MS). Husbandry Manual for West Indian Iguanas

- Michaels, C. J., Antwis, R. E., and Prezios, R. F. (2014) Manipulation of the calcium content of insectivore diets through supplementary dusting. Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research. July 2014

- Mitchell, M. and Tully, T. N. (2008) Manual of Exotic Pet Practice e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- McNaughton, S. A., and Marks, G. C. (2003) Development of a food composition database for the estimation of dietary intakes of glucosinolates, the biologically active constituents of cruciferous vegetables. British Journal of Nutrition, 90, 687–697

- NC State Veterinary Hospital Exotic Animal Medicine Department. Caring for Your Pet Bearded Dragon.

- OECD. (2015) Novel Food and Feed Safety. Safety Assessment of Foods and Feeds Derived from Transgenic Crops. Vol 2. OECD Publishing

- Oonincx, D. G. A. B., Leeuwen, J. P. van., Hendriks, W. H., and Poel, A. F. B. van der. (2015) The Diet of Free-Roaming Australian Central Bearded Dragons (Pogona vitticeps). Zoo Biology 34:271-277. Wiley Periodicals Inc.

- Peterson, M. E. (DVM), and Talcott, P. A. (2012) Small Animal Toxicology. Elsevier Health Sciences

- Pianka, Eric, R. 2005. The ecology and natural history of the dwarf bearded dragon Pogona minor in the Great Victoria Desert Australia Draco, 6(N): 63-66 Nr 22.

- Rop, O., Mlcek, J., Jurikova, T., and Neugebauerova, J. (2012) Edible Flowers-A New Promising Source of Mineral Elements in Human Nutrition. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 17. 6672-83.

- Ruana, Q., Zhenga, X., Chena., Xiaoa., Peng., Leung, D. W. M., and Liu, E. (2013) Determination of total oxalate contents of a great variety of foods commonly available in Southern China using an oxalate oxidase prepared from wheat bran. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 32(1): 6-11.

- Savage, G. P., Vanhanen, L., Mason, S. M., and Ross, A. B. (2000) Effect of Cooking on the Soluble and Insoluble Oxalate Content of Some New Zealand Foods. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 13, 201-206.

- Savage, Geoffrey & Klunklin, Warinporn. (2018) Oxalates are Found in Many Different European and Asian Foods – Effects of Cooking and Processing. Journal of Food Research. 7. 76.

- Simpson, S. Dragon Breath… Periodontal Disease in Central Bearded Dragons (Pogona vitticeps). Proceedings of the 2015 UPAV Conference, Sydney. p 47-50

- Sinha, K., and Khare, V. (2017) Review on: Antinutritional factors in vegetable crops. The Pharma Innovation Journal. 6(12): 353-358

- Spritzler, F. RD, CDE (2017) Oxalate (Oxalic Acid): Good or Bad? Healthline

- Stahl, S. (1999) General Husbandry and Captive Propagation of Bearded Dragons, Pogona vitticeps. Bulletin of the Association of Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians. Care in Captivity. 9(4) pp 12-17

- Stahl, S., and Donoghue, S. (2010) Nutrition of Reptiles. In: Hand MS, Thatcher CD, Remillard RL, et al, editors. Small Animal Clinical Nutrition. Topeka (KS): Mark Morris Institute pp 1237-1249

- Thompson, K. S. (2016) Applied Nutritional Studies with Zoological Reptiles. (Doctoral Dissertation) Oklahoma State University

- Thompson, S. A., & Thompson, G. G. (2003) The western bearded dragon, Pogona minor (Squamata: Agamidae): An early lizard coloniser of rehabilitated areas. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 86, pp 1-6.

- Tsai, J., Huang, J., Wu, T. T., and Lee, Y. H. (2005) Comparison of Oxalate Content in Foods and Beverages in Taiwan. JTUA 16(3)

- UCDavis (2019) Bearded Dragon Care. UCDavis School of Veterinary Medicine

- USDA Food Composition Database

- Vieites-Outes, C., López-Hernández, J., & Asunción Lage-Yusty, M. (2016) Modification of glucosinolates in turnip greens (Brassica rapa subsp. rapa L.) subjected to culinary heat processes, CyTA – Journal of Food, 14(4): 536-540

- Voe, R. S. (2014) Nutritional Support of Reptile Patients. Vet Clinic Exotic Animals 17 pp 249–261

- Vu Hong Ha, N. (2012) Oxalate and Antioxidant Concentrations of Locally Grown and Imported Fruit in New Zealand Thesis Doctor of Philosophy for Lincoln University

- Wotherspoon, D., and Burgin, S. 2010. Allometric variation among juvenile, adult male and female eastern bearded dragons Pogona barbata (Cuvier, 1829), with comments on the behavioural implications. Zoology (Jena, Germany) 114, 23–28.

- Wotherspoon, D., and Burgin, S. 2016. Sex and ontogenetic dietary shift in Pogona barbata, the Australian eastern bearded dragon. Australian Journal of Zoology 64, 14-20.

- Wotherspoon, A. D. (2007). Ecology and management of Eastern bearded dragon : Pogona barbata. Thesis, University of Western Sydney, Richmond. Retrieved from University of Western Sydney Library.

- Zarembski, P. M. & Hodgkinson, A. (1962) The oxalic acid content of English diets. British Journal of Nutrition 16: pp 627

Source: https://beardeddragonsworld.com/bearded-dragon-diet/

0 Response to "Do You Have to Feed a Bearded Dragon Live Food"

Post a Comment